Just a quick note to convey my brimming enthusiasm and optimism about movies this year, even as we are headed into summer blockbuster season, a time that often has disadvantages for strong, well written films. This years crop looks outstanding.

The year 2013 is shaping up to be quite a fine one for film. Already I've seen an ambitious and epic indie in "The Place Beyond the Pines" and a genuine brain-teaser from Shane Carruth (of "Primer") in "Upstream Color," which I feel remarkably unqualified to write about (Mr. Overstreet, a critic I greatly respect, appears to have liked it more unequivocally than I did). Like "Primer," I understood on first viewing only the broadest brushstrokes of plot and emotion. (Let me put it this way: Pigs and bugs and sound effects and mind control are involved.) I'm not even sure I can say whether I liked it or not. Perhaps, like with "Primer," I'll be more clear on such basic things if I see it again. And this weekend sees the limited release of another indie that looks promising to me: "Mud," from Jeff Nichols, director of the wonderful "Take Shelter" and "Shotgun Stories."

I've also watched a big and bold, but also intelligent and beautiful sci-fi picture, "Oblivion," which I'll touch on briefly here. (I might write a full review eventually, but certainly not before I see it again.) It stars Tom Cruise, who despite being an actor I'm not particularly drawn to, has undeniably been on a roll with this and the spectacular "Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol" last year. It also is the rare modern science fiction movie that throws in interesting ideas and real emotions along with its superb visuals and high-flying chase scenes. And it has an honest-to-goodness real live third act, one which is not given away by the trailer. I walked in thinking I had the movie basically figured out, and was pleasantly surprised to discover otherwise. Also in the sci-fi department, we will soon have the newest J.J. Abrams "Star Trek" film, the interesting casting of which I wrote about here.

There's also been a new Terrence Malick film released, less than two years after "Tree of Life," which is really something considering Malick has been known to on occasion go twenty years between movies. I've yet to see Malick's "To the Wonder," so I clearly can't recommend it point blank, but on the strength of "Tree of Life" and "Days of Heaven," I'm certainly interested.

Joss Whedon will be revealing his take on Shakespeare, filmed entirely in and around his own house with handpicked actors who will be familiar to those familiar with Whedon's past work. Whedon and Shakespeare seem like a splendid match, so their "Much Ado About Nothing" could be one to keep an eye on.

We'll also be getting what looks to be a fantastic summer (and fall) full of superhero movies:

-"Iron Man 3"

-"Man of Steel"

-"Wolverine"

-"Thor: The Dark World"

Also, this Christmas season we will get the second part of Peter Jackson's lengthy adaptation of The Hobbit, for which there is no trailer yet.

You'll notice quite the array of different types of movies here. It is a good time to be a movie lover. I for one am incredibly, perhaps unreasonably, excited.

Friday, April 26, 2013

Saturday, April 20, 2013

The Place Beyond the Pines

"If you ride like lightning, you're going to crash like thunder."

Some films take over my head, replaying themselves vividly in my mind's eye and dominating large swaths of my waking thoughts. These tend to be films with either dense and complex narratives (like "Inception"), or unique and arresting visual displays and cinematography (like "The Fall" or "Tree of Life"), or both (like "The Prestige"). But other films linger in the back corners of my consciousness, and their power seems a bit harder to pinpoint. Derek Cianfrance's remarkable "The Place Beyond the Pines" is such a film, and it has been lurking in my head for a week now, haunting me with its ambition, simplicity, and deep melancholy.

I want to convey some sense of why this film is powerful, and at the same time I don't want to give away the emotional and structural surprises up its splendid sleeve, so I'm going to tread carefully here, and also warn you against reading plot-heavy reviews or synopses if you want to see the film unspoiled, because it is rather difficult to talk about it in-depth without giving away certain aspects of the story which are probably better left for the viewer to discover.

"The Place Beyond the Pines" stars Ryan Gosling as Luke, a carnival stunt biker who discovers he has a son by way of old fling Romina (Eva Mendes). To his credit, he decides he wants to be involved in their lives, and quits the carnival so he can stay in town. The way he goes about providing for this makeshift family from there, however, quickly becomes somewhat less than admirable, and less than legal, to put it mildly. Gosling gives easily the best performance in the film, projecting at once both a reckless outlaw cool and an intense emotional vulnerability. A nice visual touch that neatly summarizes the captivating duality of the performance is the tattoo at the corner of his eye that looks like a teardrop, until you look closer and see that is in fact a dagger dripping blood. Here is an utterly convincing portrayal of a man who can show incredible gentleness and sweetness giving his baby son ice cream for the very first time, and then a couple sequences later be screaming hoarse profanities at the petrified employees of a bank he is robbing. (See! I'm already giving things away!) The great thing though is that you can hear the rising panic and desperation in his voice in those same screams, the fear of a man who may have a perfect and daring plan for his heist, but on the other hand may not have what it takes emotionally for a sustained life of crime.

The now seemingly omnipresent Bradley Cooper co-stars, but the less I say about his role in things the better. He carries it off well though. (Who would have thought that the earnest and unlucky reporter from "Alias" would ever end up being a major Hollywood star and Academy Award nominee?) Mendes also gives a fine performance, but her role as Romina, though incredibly sympathetic, is much less developed (as is too often the case with female roles) and she gets a bit less screen time. Australian actor Ben Mendelsohn brings a weary slyness to his part as a workaday criminal who may also be playing, unaware, the part of a devil in the larger drama around him. Just listen to the music when he and Luke meet in a sunny but ominous clearing in the woods. The way Cianfrance is able to use this character both as a perfectly commonplace albeit opportunistic criminal, someone I was absolutely convinced I could find in the real world, and also simultaneously as a symbolic figure of dark temptation, is emblematic of the way the film as a whole works, functioning at once both as realism and as heightened epic, with the weight of some forgotten Greek or Shakespearean tragedy that has been shifted seamlessly into a modern environment. The alternately gritty and soaring cinematography works together with the gorgeous score to help accomplish this. The former grounds us in the real, specific, detailed day-to-day world, while the latter ties the characters and the themes together and emphasizes the scope and the emotional weight of the events. Ordinary moments are thus imbued with chilled majesty, and certain shot/score combinations held me entranced. Combined with sharp writing and acting, this results in everything that transpires feeling fated, and yet always dependent on the choices of these profoundly screwed up characters. I could have sworn this was an adaptation of a great undiscovered novel, but no, the whole thing is an original script by Cianfrance and his co-writers Ben Coccio and Darius Marder.

Again wording things carefully, I'll simply mention the fact that the film is divided roughly into thirds, and that this division has advantages and disadvantages. For one thing, the structure often makes it hard to tell where the story, or any given arc within it, is headed. This unpredictability lends an air of intensity and realism—anything could happen!—but also at times left me feeling adrift, unconnected to the plot. Only at the end could I see what it was building too. And frankly, the last third does not, for my money, quite live up to what precedes it. It fails to fully capitalize on and bring full circle all the emotions and sense of grandeur instilled by the first sections and the generally ambitious nature of the film. In fact, to put it harshly, the three acts of the story are each slightly less compelling than the one that came before, when they should be building on each other's successes. Nonetheless, "The Place Beyond the Pines" is a strong and fiercely emotional film about fathers, sons, violence, and generational consequences.

"The Place Beyond the Pines" (R) ***1/2

Note: This film was on limited release, but just this week got a wider release, so the likelihood that it is available in a theater near you just went up significantly.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

On heroes, villains, and demographics.

It recently occurred to me that in addition to more structured writing such as film reviews or stories, I also gave the impression that I would be offering random snippets of my thoughts on this blog, and that I have not really been doing so. In that vein, some thoughts on casting in the highly anticipated but awkwardly titled "Star Trek Into Darkness." http://trailers.apple.com/trailers/paramount/startrekintodarkness/

Now before I go any further, I should clarify my position on the film in general, as much as that is possible having not seen it yet. I am very much looking forward to this movie. J.J. Abrams' franchise reboot with the 2009 "Star Trek" was solid, likeable, and completely entertaining. With pitch-perfect recasting of iconic roles, it reinvigorated a series bogged down by its own storied history and high-handed humanist pretensions. Still, I'd go short of calling it the brilliant, unqualified success that some heralded it as. There was, for me at least, the air of something lacking. There was a certain weightlessness to the events, even when planets were being destroyed, that made it feel like an unmistakably minor work. And "Into Darkness" looks to correct all that with a more frankly emotional, dangerous, and, for lack of a better word, dark storyline. Plus, it has Benedict Cumberbatch, who is fantastic in BBC's "Sherlock," and who I fully expect will give a terrific performance here as the powerful and villainous, if blandly named (if that is indeed his real name), John Harrison.

That brings me, belatedly, to the point of this rather rambling train of thought. An interesting note about this movie is that the primary villain will be a young white sane male human. Something felt unusual about the concept of "Into Darkness" in my mind, and I kept coming back to this point until I realized why it stuck out: A young white sane male human as the main villain is rather rare in action/sci-fi movies. Think about it for a moment. In fact, I want to suggest that its rareness is directly related to the commonness of a young white sane male human as the main hero of such movies. Usually the villain in such movies is different from the hero in at least one of these five ways:

(1) The villain is significantly older than the hero, in order to give him more gravitas in comparison with the young, brash protagonist. A prime example is Bond movies, where the classic villain is an old man in a chair with a cat and a diabolical scheme for world domination. Having your villain be, if not quite senior citizen material, at least in the middle-aged department, also has the advantage of allowing the casting of a veteran actor with proven experience and an air of authority. To see evidence of why this works so well, think of the primary villains, and their respective actors, from "Batman Begins," "Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl," "Spider-Man"s 1, 2, and Amazing, all the Damon "Bourne" movies (Cooper, Strathairn, Cox, Finney, what a round-up!), "Mission Impossible"s 1 and 4, "Star Wars" episodes 2-6, "Superman," and countless more. This can, of course, be flipped on its head, such as in various movies where the hero is played by a now older actor like Michael Caine, Liam Neeson, Bruce Willis, Sylvester Stallone, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, and faces off against a younger villain. Expect a lot of jokes about how freakishly old the protagonist is. "Red" is a prominent recent example of this inversion. The point is, there's a substantial age difference between the hero and the villain.

(2) The villain is a minority, or close minority stand-in (read very humanoid alien) to give a dangerous sense of "other"-ness. Hollywood has perhaps been trying to move away from this of late, sheepishly aware of its own rather racist past, but it is definitely still a factor. It seems to me that the most common new way to go about this often involves making the villain an aggrieved and thus somewhat sympathetic figure, one who has legitimate grievances, which has the advantage of raising moral dilemmas, calling the hero's ideology into question, and creating a more complicated and compelling antagonist figure. This trope sometimes pops up in cop shows, but it also still occurs form time to time in movies. Think Denzel Washington in "Training Day," who was street-smart and charismatic; Javier Bardem in "Skyfall," who was betrayed by his boss/mother figure; the Klingons, who had their own fully developed culture and were pretty much the coolest people in the galaxy; Khan in "Wrath of Khan," who had been stranded by Star Fleet (if memory serves); and Nero in the latest "Star Trek," who had his own planet destroyed before he decided he needed to do the same thing to Spock. (Notice that Star Trek movies seems to do this a lot.) Loki from "Thor" is another example; although he looks a lot like Thor, he is really the child of a frost giant, and he has a massive chip on his shoulder about it, but somehow remains a somewhat sympathetic villain. This minority villain/majority hero tendency can also be turned on its head. A notable example of such an inversion is Michael Mann's "Collateral," in which down-on-his-luck African American cabbie Max, played by Jaimie Foxx, is terrorized, but also oddly championed and taught confidence by, merciless white successful-businessman-like assassin Vincent, played by Tom Cruise. Again, the point is that the hero and villain are often on the opposite side of a race/ethnicity line.

(3) Similarly, but less commonly, the hero and villain can be on opposite sides of a gender divide, which usually plays on sexual tension of some sort, with either an evil seductress tempting the hero to abandon virtue or faithfulness, or a heroine facing off against a physically stronger male villain with the threat of rape present or lurking in the background. See Grendel's mother in "Beowulf" and (SPOILERS) Miranda Tate/Talia al'Ghul in "Dark Knight Rises," a stealth example, since for most of the movie she does not appear to be the main villain (END SPOILERS) for examples of the former, and pretty much every slasher/home invasion movie ever made for examples of the latter.

(4) Taking the minority angle further, and in a less potentially confusable-for-racism direction, the villain is of an entirely different species than the hero. This one's pretty simple. It stems from classic monster stories, and draws on our very basic human fear of things out there in the woods that want to eat us, rip us apart, and kill us, preferably not in that order. Think any sort of vicious animal or alien that is not very humanoid. Classic examples include: the alien from "Alien," Godzilla from "Godzilla," the jaws from "Jaws," the Terminator from "Terminator," the creature from the black lagoon from "The Creature from the Black Lagoon," etc. etc. As you might suspect, this too can occasionally be inverted, in which case you usually end up with a movie that features a cute little monster/alien/robot running from evil human authority figures with the one little human who understands him/her/it. For a prime example, I'll give you a hint: it begins with the letter E and ends with the letter T.

(5) The villain is crazy. Especially in this age of widely-publicized senseless violence against children and other civilians, this is one is very scary and effective, because we see evil that is hard to explain rationally in the real world too. There is no war or profit motive, or even any particularly relevant backstory that would adequately explain this type of villain. The villain is just nuts, no other explanation offered or needed. Jack Nicholson's Joker from "Batman" is mentally unbalanced. Heath Ledger's Joker from "The Dark Knight" is mentally unbalanced, to say the least. (Though he does seem to have something of an ideology he's trying to prove.) In contrast, and for fairly obvious reasons, the hero is usually not crazy. (Or IS he? Dun dun dun!) Any which way, the hero and the villain are separated (at least apparently) by the sanity/insanity line, which makes for a stark contrast.

Circling around back to Star Trek, I'd like to point out (though you've probably already noticed where I'm going with this) that Cumberbatch's John Harrison has NONE of these major distinguishing differences from Chris Pine's Captain Kirk. Demographically, they are interchangeable. If they were filling out demographic stats on themselves for a poll or a census, they would be practically identical. Additionally, Cumberbatch usually plays heroes (voice acting in The Hobbit adaptations aside). I guess what I'm saying is, it is highly unusual to have the main villain be so similar, demographically-speaking, to the main hero. Most villains could claim at least one of the points listed above that would distinguish them from the hero. This John Harrison fellow is thus a remarkable irregularity from most cinematic villains, at least in large-scale action movies.

Of course, the Star Trek franchise has played with similarities between its heroes and villains before, most notably with Tom Hardy as the villain of "Star Trek: Nemesis," who, while admittedly much younger than Picard, was in fact his clone. The choices of each reflected directly on the other. I wonder if there will be a similarly strong parallel made in "Into Darkness" between John Harrison and Kirk? Will they be revealed to be two sides of the same Federation-trained coin? I'm interested in finding out, whenever I see "Into Darkness," which is coming out in May. Let me know what you think!

Now before I go any further, I should clarify my position on the film in general, as much as that is possible having not seen it yet. I am very much looking forward to this movie. J.J. Abrams' franchise reboot with the 2009 "Star Trek" was solid, likeable, and completely entertaining. With pitch-perfect recasting of iconic roles, it reinvigorated a series bogged down by its own storied history and high-handed humanist pretensions. Still, I'd go short of calling it the brilliant, unqualified success that some heralded it as. There was, for me at least, the air of something lacking. There was a certain weightlessness to the events, even when planets were being destroyed, that made it feel like an unmistakably minor work. And "Into Darkness" looks to correct all that with a more frankly emotional, dangerous, and, for lack of a better word, dark storyline. Plus, it has Benedict Cumberbatch, who is fantastic in BBC's "Sherlock," and who I fully expect will give a terrific performance here as the powerful and villainous, if blandly named (if that is indeed his real name), John Harrison.

That brings me, belatedly, to the point of this rather rambling train of thought. An interesting note about this movie is that the primary villain will be a young white sane male human. Something felt unusual about the concept of "Into Darkness" in my mind, and I kept coming back to this point until I realized why it stuck out: A young white sane male human as the main villain is rather rare in action/sci-fi movies. Think about it for a moment. In fact, I want to suggest that its rareness is directly related to the commonness of a young white sane male human as the main hero of such movies. Usually the villain in such movies is different from the hero in at least one of these five ways:

(1) The villain is significantly older than the hero, in order to give him more gravitas in comparison with the young, brash protagonist. A prime example is Bond movies, where the classic villain is an old man in a chair with a cat and a diabolical scheme for world domination. Having your villain be, if not quite senior citizen material, at least in the middle-aged department, also has the advantage of allowing the casting of a veteran actor with proven experience and an air of authority. To see evidence of why this works so well, think of the primary villains, and their respective actors, from "Batman Begins," "Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl," "Spider-Man"s 1, 2, and Amazing, all the Damon "Bourne" movies (Cooper, Strathairn, Cox, Finney, what a round-up!), "Mission Impossible"s 1 and 4, "Star Wars" episodes 2-6, "Superman," and countless more. This can, of course, be flipped on its head, such as in various movies where the hero is played by a now older actor like Michael Caine, Liam Neeson, Bruce Willis, Sylvester Stallone, or Arnold Schwarzenegger, and faces off against a younger villain. Expect a lot of jokes about how freakishly old the protagonist is. "Red" is a prominent recent example of this inversion. The point is, there's a substantial age difference between the hero and the villain.

(2) The villain is a minority, or close minority stand-in (read very humanoid alien) to give a dangerous sense of "other"-ness. Hollywood has perhaps been trying to move away from this of late, sheepishly aware of its own rather racist past, but it is definitely still a factor. It seems to me that the most common new way to go about this often involves making the villain an aggrieved and thus somewhat sympathetic figure, one who has legitimate grievances, which has the advantage of raising moral dilemmas, calling the hero's ideology into question, and creating a more complicated and compelling antagonist figure. This trope sometimes pops up in cop shows, but it also still occurs form time to time in movies. Think Denzel Washington in "Training Day," who was street-smart and charismatic; Javier Bardem in "Skyfall," who was betrayed by his boss/mother figure; the Klingons, who had their own fully developed culture and were pretty much the coolest people in the galaxy; Khan in "Wrath of Khan," who had been stranded by Star Fleet (if memory serves); and Nero in the latest "Star Trek," who had his own planet destroyed before he decided he needed to do the same thing to Spock. (Notice that Star Trek movies seems to do this a lot.) Loki from "Thor" is another example; although he looks a lot like Thor, he is really the child of a frost giant, and he has a massive chip on his shoulder about it, but somehow remains a somewhat sympathetic villain. This minority villain/majority hero tendency can also be turned on its head. A notable example of such an inversion is Michael Mann's "Collateral," in which down-on-his-luck African American cabbie Max, played by Jaimie Foxx, is terrorized, but also oddly championed and taught confidence by, merciless white successful-businessman-like assassin Vincent, played by Tom Cruise. Again, the point is that the hero and villain are often on the opposite side of a race/ethnicity line.

(3) Similarly, but less commonly, the hero and villain can be on opposite sides of a gender divide, which usually plays on sexual tension of some sort, with either an evil seductress tempting the hero to abandon virtue or faithfulness, or a heroine facing off against a physically stronger male villain with the threat of rape present or lurking in the background. See Grendel's mother in "Beowulf" and (SPOILERS) Miranda Tate/Talia al'Ghul in "Dark Knight Rises," a stealth example, since for most of the movie she does not appear to be the main villain (END SPOILERS) for examples of the former, and pretty much every slasher/home invasion movie ever made for examples of the latter.

(4) Taking the minority angle further, and in a less potentially confusable-for-racism direction, the villain is of an entirely different species than the hero. This one's pretty simple. It stems from classic monster stories, and draws on our very basic human fear of things out there in the woods that want to eat us, rip us apart, and kill us, preferably not in that order. Think any sort of vicious animal or alien that is not very humanoid. Classic examples include: the alien from "Alien," Godzilla from "Godzilla," the jaws from "Jaws," the Terminator from "Terminator," the creature from the black lagoon from "The Creature from the Black Lagoon," etc. etc. As you might suspect, this too can occasionally be inverted, in which case you usually end up with a movie that features a cute little monster/alien/robot running from evil human authority figures with the one little human who understands him/her/it. For a prime example, I'll give you a hint: it begins with the letter E and ends with the letter T.

(5) The villain is crazy. Especially in this age of widely-publicized senseless violence against children and other civilians, this is one is very scary and effective, because we see evil that is hard to explain rationally in the real world too. There is no war or profit motive, or even any particularly relevant backstory that would adequately explain this type of villain. The villain is just nuts, no other explanation offered or needed. Jack Nicholson's Joker from "Batman" is mentally unbalanced. Heath Ledger's Joker from "The Dark Knight" is mentally unbalanced, to say the least. (Though he does seem to have something of an ideology he's trying to prove.) In contrast, and for fairly obvious reasons, the hero is usually not crazy. (Or IS he? Dun dun dun!) Any which way, the hero and the villain are separated (at least apparently) by the sanity/insanity line, which makes for a stark contrast.

Circling around back to Star Trek, I'd like to point out (though you've probably already noticed where I'm going with this) that Cumberbatch's John Harrison has NONE of these major distinguishing differences from Chris Pine's Captain Kirk. Demographically, they are interchangeable. If they were filling out demographic stats on themselves for a poll or a census, they would be practically identical. Additionally, Cumberbatch usually plays heroes (voice acting in The Hobbit adaptations aside). I guess what I'm saying is, it is highly unusual to have the main villain be so similar, demographically-speaking, to the main hero. Most villains could claim at least one of the points listed above that would distinguish them from the hero. This John Harrison fellow is thus a remarkable irregularity from most cinematic villains, at least in large-scale action movies.

Of course, the Star Trek franchise has played with similarities between its heroes and villains before, most notably with Tom Hardy as the villain of "Star Trek: Nemesis," who, while admittedly much younger than Picard, was in fact his clone. The choices of each reflected directly on the other. I wonder if there will be a similarly strong parallel made in "Into Darkness" between John Harrison and Kirk? Will they be revealed to be two sides of the same Federation-trained coin? I'm interested in finding out, whenever I see "Into Darkness," which is coming out in May. Let me know what you think!

Sunday, April 14, 2013

Moon

“Moon” stars Sam Rockwell, an actor who displayed terrific talent both in “Galaxy Quest” (the terrific spoof that is like the “Princess Bride” of science fiction) and in Ridley Scott’s “Matchstick Men.” In this movie, he plays Sam Bell, a solitary worker on a mining base on the moon. He misses his family, who he can only talk to via slow and unreliable recorded video messages. The presence of a smiley-face robot named Gerty (voiced by Kevin Spacey) is useful, but not very reassuring to us in the audience if we remember “2001: Space Odyssey.” Neither does the machine offer much comfort to poor Sam Bell, although it could be given credit for trying. Sam has been up on the moon base for a long time; in the opening scenes we see him with a thick and untamed beard, an unusual look for Mr. Rockwell which serves to underline how long he has been up there. He has been isolated so long, in fact, that his sanity is clearly on edge. This makes the events that follow (which I will try not to give away, although the trailer spoils a bit of the plot) all the more interesting, because we are always wondering how mentally stable Sam really is. He does hallucinate, and recognizes it, so we have to question whether some other strange things that go on might be hallucinations too. It also may not surprise you that his employers are not entirely to be trusted, and everything is definitely not as it seems.

This fits the type of story I love: tight, contained, suspenseful, character-based dramas. Even better, it is science fiction, a genre I have a weak spot for, and “hard” science fiction at that—it feels realistic, and could probably be based on some simple extrapolations from current science and technology. Too many science fiction movies these days are nothing but gunfights and explosions, just action movies (good or bad) dressed up in sci-fi clothes. This one is intelligent and subtle, for which I must give it credit. And Sam Rockwell gives a terrific performance as this lonely, insecure, unstable man, who may know much less about himself and his situation than he at first appears to. He is the only actor on the screen for easily 95% of the movie, and he carries it off just fine. (Although, thinking about it, I have to say Will Smith did a better job of winning over my sympathy with his one-man-wonder portrayal of loneliness in “I Am Legend.” But maybe that’s just because he had the advantage of possessing the almost invulnerable charisma of Will Smith. Or maybe it was because he had a dog instead of a robot.)

So why didn’t this film quite click with me? Despite all the twists and the thoughtful turns and introspection, and the logical consistency of the story, I was left cold at the end. I guess I’m left wondering what the larger truth behind this movie is, other than the frankly self-evident ones that loneliness stinks, and can drive someone to the edge of madness. There’s also a feeling of incompleteness, that perhaps the real story, with higher stakes and more character interaction, might be actually just about to begin. And “Moon” could have perhaps gone further with its premise. I expected it to ratchet up a couple levels of crazy further than it did. So, in the end, while I might have a crush on the concept and careful execution of this movie, I have yet to locate a heart or a truth that could take it from competent to great. For anyone out there who has seen this, I would love to be proven wrong.

"Moon" (2009) **1/2

Monday, April 8, 2013

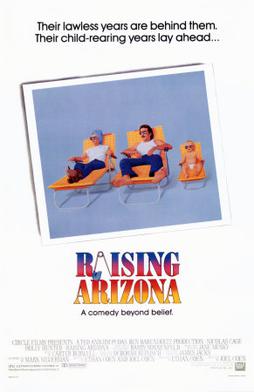

Hidden Gems of Netflix: Raising Arizona

"It's a craaazy world."

"Someone oughta sell tickets."

Overall I find myself harboring mixed feelings about the work of the Coen brothers. They are clearly possessed of excellent craftsmanship, yet while their films are always fascinating and entertaining at the very least, there seems to lurk beneath the surface of most of them a certain cynicism. Some of their harshest critics accuse them of being out-and-out misanthropes, perhaps snickering up their sleeves at the often hapless characters that inhabit their tonally patchy and sometimes abruptly absurd stories. And I can see that this line of reasoning could indeed be applied to some portion of their oeuvre. Still, I will not go nearly so far as to say that such injurious appellations as misanthropy properly reflect each and every one of their films indiscriminately.

And thus I want to champion an early example of a film of the brothers Coen that has genuine heart and optimism. I dare to suggest that "Raising Arizona" (being the second film by said brothers, and being the chief subject of this review), represents their most sincere effort to come alongside their screwed-up screwball characters. In H.I. and Edwina (Nicholas Cage and Holly Hunter), the repeat offender criminal and the policewoman he marries, they proffer protagonists who are at once woefully incompetent and deeply sympathetic. For this oddest of odd couples have a persistent, ingrained, and emotional desire to have a child, but Ed is barren. The farcical plot of the film is launched (after a splendidly paced opening that introduces these characters to the audience and each other), by this most primal, natural, and Biblical of human desires, and by the desperate and criminal plan that the two dream up to fulfill the glaring lack in their newly minted domestic life. Because of H.I.'s criminal past they cannot adopt, so they decide to steal a baby, one of the Arizona quintuplets.

This rash act—which the film readily admits through H.I.'s earnest though somewhat torpid narration is not such a great idea—leads to a multitude of problems, not the least of which is that neither of these two would-be parents really know how to take care of a baby. Their ineptitude fuels much of the comedy, but at the same time we are shown that though they are clearly misguided (can there even be comedies about sane, reasonable people?), they love this kidnapped kid and they love each other. The other main difficulty they encounter stems from the fact that almost everyone in the wacky world of "Raising Arizona" is a would-be parent. Nathan Jr. the missing Arizona boy is in very high demand, and H.I. and Ed are soon surrounded by alternately quirky and over-the-top criminal elements, comically determined and hell-bent on the baby himself and the reward money respectively. Both of these elements link back directly to the hapless and continually flustered H.I.: two of his prison friends break out and want to hole up in his house, and his nightmares predict and/or produce a ridiculous bounty hunter outlaw, the grenade-loving, small-animal-obliterating Lone Biker of the Apocalypse, whose visual introduction very much lives up to that title. The Coens clever script makes plain that this figure of almost abstract macho evil (the farcical forerunner of Javier Bardem's stone-faced killer in "No Country for Old Men"?) is the embodiment of the bad and criminal tendencies that keep pulling H.I. back in, and the danger in which he thus puts his fragile new family. This tangle of conscience, consequences, and comic catastrophe builds slowly but surely to several great scenes: a fantastic whirling slapstick set-piece that keeps doubling back on itself, a genuinely touching emotional and moral reckoning, and an intense and bizarre showdown involving guns, grenades, and a revelatory tattoo. The films final moments express a graceful and sincere hopefulness that is incredibly refreshing.

And thus, to my pleasant surprise, I can report that the famously sarcastic and weird Coen brothers have smuggled within the undeniable oddness of "Raising Arizona"—a goofy and misshapen crime dramedy farce—a thoughtful reflection on parenthood and responsibility.

"Raising Arizona" (PG-13) **** (Available on Netflix Instant)

Vantage Point

When people say a movie is “non-stop action,” they don’t

mean it. The phrase is a useful hyperbole used to describe films that have intense

action scenes in them. Because of how "Vantage Point" is structured, it

really does become non-stop action. A terrorist act is displayed early on, and

then the movie dances around explaining repercussions from different angles for

the rest of its length. From the point when that crucial explosion occurs on, the movie does not let up. By the

end, this becomes exhausting, and the movie feels much longer than it actually is. It does not help that the

performances are not great. Dennis Quaid does his best with the underwritten

role of a body guard with an Important Past full of Regrets. He emotes well and

has a desperate energy, and he wins our sympathy, and so holds the movie together

more than it deserves. We care, because we sense his innate decency. However,

Sigourney Weaver is wasted here in the role of a news producer. Her character

goes nowhere, and I wondered if she was added so the cameraman could film

something while the other actors were desperately trying to catch their breath

between takes. Forest Whitaker is merely passable here as a tourist with a

video-camera and a sense of urgent compassion. The script gives him no other

traits. William Hurt, a great actor in the right part, is also sadly wasted as

the US president. You would think it would be an important role in this kind of

movie, but he is allowed barely any screen time. Finally, the terrorists are

rather unbelievable. They are always five steps ahead of everyone else. Their

reasons for the act of terrorism are alluded to, but never fully fleshed out. Yet

somehow, against all odds, this film was entertaining. The never-let-up pace

didn’t let me think about the problems with the movie while watching it. And

the gimmick of showing multiple angles did add an air of mystery, and somewhat

covered up for the fact that other elements of style, like good camerawork,

were mostly absent. So this movie basically worked, despite the leaky script and barely-there

performances from its leads. I wouldn't exactly suggest going out of your way to find it, but if you're in the mood for something exciting and mostly mindless, and you're wandering around one of those stubbornly lingering movie rental stores, there are certainly worse options than the tense and somewhat loopy thriller "Vantage Point." How's that for a recommendation?

"Vantage Point" (PG-13) ***

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)